Needle Drop at Midnight

Vibe: caper‑noir, neon city, quick banter, zero spice Logline: A midnight note lures a record‑shop owner into a small, elegant heist of provenance—returning the right record to the right room.

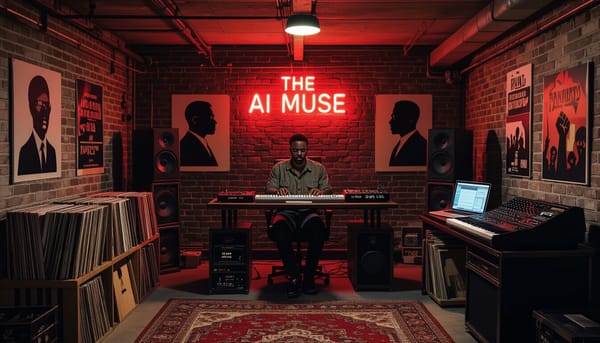

The neon sign over the door buzzed like a fruit fly with opinions: THE AI MUSE in pink, “Records & Rare Finds” in a blue that refused to pick a decade. I was counting the till and telling the shop plant not to die on my watch when the bell chimed after closing.

“Sorry, we’re—” I started, then stopped. No one. Just the front mat, curling at one corner like a cat’s ear, and a square of brown paper on the counter where there hadn’t been one.

The note was typed on a real machine, the letters a little drunk around the edges.

PLAY TRACK 7 AT 12:07. DO NOT SKIP. — L

Cute. Midnight riddles. It was 11:41, the hour when I usually stacked new arrivals into half-sensible sections: Soulful With Opinions, EDM But Friendly, and Whatever That Was Please Alphabetize By Courage.

I flipped the note. On the back: a simple map of the shop. A dot where the listening station was. An X by the jazz section. Whoever L was had neat penmanship and a flair for drama. Unfortunately for them, I did too.

The listening station wore a thrifted pair of headphones with clean foam. I sanitized them like a good citizen and cued up the top record on the spindle: CITY GHOSTS – NIGHT BUS EDITS. Track 7 was called “Horizon Room.” I smiled despite myself. A coincidence, but charming.

At exactly 12:07, the bass slipped in like a conversation starter. The track was one of those slow buildups that makes your shoulders feel like they were designed on purpose. That’s when the second note arrived, not on paper but as a whisper through the shop speakers.

“Check the Jimmy Smith bin, sleeve number two from the right,” a voice said. Not creepy. Not synthetic. A woman, precise vowels, humor bracketed.

I looked up at the ceiling. “You have the wrong girl if you’re trying to haunt me, L,” I said to the track like a fool. I walked to jazz anyway.

Sleeve two from the right was a copy of The Sermon!, a little tired around the corners. Inside, another note:

THIS IS A DRY RUN. REAL THING AT 12:19. TRUST THE PROCESS. — L

Behind it: a locker key, the sort people lose at pools.

I turned the shop key in the deadbolt out of habit; I don’t know why I expected it to help. The city outside made its own music—tires on wet pavement, a bus sighing, late laughter—the usual mixtape. I checked the corners, then checked my nerves. Steady. I was annoyed and entertained in equal measure, which for me counts as brave.

At 12:19, the overhead speaker crackled like a throat clearing. “Hello, Needle,” said the same woman. “May I call you Needle? It’s friendlier than ‘shop owner.’”

“Only if I can call you Luddite,” I said, because the typewriting. “And only if you tell me how you’re routing your little intercom trick.”

“Counter mic,” she said. “From the days when customers would do blind tests. It’s still wired, and your back speaker is live. I’m in the alley.”

I turned toward the rear exit. “Bold of you to tell me your location, L.”

“Bold of you to keep listening,” she said. I heard the smile. “Locker 27 at Maple Storage. Two blocks south. The key in your hand fits it.”

“Let me guess,” I said. “There’s a treasure.”

“A test,” she said. “Treasure is for pirates. You interested?”

“I don’t run midnight errands for voices,” I said, which was a lie on at least two levels. “What’s in the box?”

“A record that wants to come home,” she said. “A 1977 private press funk LP. ‘Side B: The Elevator Doesn’t Stop Here.’ One of twenty. Stolen during a collection move from this very shop. Three owners ago. You have its siblings on your wall, left of the register.”

I looked. The wall of Greys—rare local pressings in matte sleeves. There was indeed a tiny gap between two framed LPs that I had chalked up to crooked hanging. My stomach did a small stunt. “If this is a prank,” I said, “it’s expensive.”

“Good pranks are,” she said. “I’ll owe you a better explanation after. For now: locker 27. Bring your best poker face.”

“Why me?” I asked.

“Because you catalog like a poet and count like an auditor,” she said. “Because you refuse to sell anything to people who call vinyl ‘vinyls.’ Because you water the plant like it’s a unionized employee.”

“I do none of those things,” I said, watering can already in my hand.

“You do,” L said, not unkindly. “Be back in twelve minutes. I’ll cue track seven again at :31 to mark time. Don’t run.”

I locked the shop and slid into the night without feeling particularly foolish. Two blocks south, Maple Storage thought highly enough of itself to call the hallway “The Galleria” on a laminated sign. Locker 27 opened like it had been practicing.

Inside: packing foam, a smell like old paper, and a single milk crate. On top: a Polaroid of my shop window taken from the street, neon blinking. Under that: the record. No title on the jacket, just a stamp: ELEVATOR.

“Is this the part where you spring a man with a clipboard on me?” I asked the empty air.

The fluorescent hummed. A spider considered me from a corner in a way I chose not to interpret.

Back at the shop at 12:31, the bell chimed like it wanted to be a plot point. L’s voice came cool as a librarian.

“Set it on the counter, Needle. Let’s begin the exam.”

“You could start with hello,” I said.

“Hello,” she said. “I am not a thief. I’m an archivist. I specialize in returning the right things to the right rooms. Tonight I needed help. Now, step one: confirm the weight.”

I weighed the jacket the way we weigh all the special ones—flat on the postal scale because it’s honest. “Seven ounces with the sleeve,” I said.

“Correct,” she said. “Step two: confirm the tell.”

“Tell?”

“The shop three owners ago used a pencil mark in the upper left corner of jackets—tiny slash. It would have faded to feint by now.”

I held the sleeve to the desk lamp. There it was: the faintest shadow of a habit. “Okay,” I said, “you’re either you, or you did very good homework as a prankster.”

“I am very good,” she said, which somehow wasn’t bragging.

I slid the record from the sleeve. Black so shiny it almost hurt. The runout groove had a message scratched lightly: DON’T WAIT FOR THE BELL.

“Cute,” I said.

“True,” she said. “Play the first thirty seconds on low, low volume. Then we put it to bed.”

I did, and the room did that thing it does when a frequency fits: it gathered itself. The opener was bass like a conversation with the floor. Then, somewhere under it, the soft double-tap of hotel desk bells.

I cut it.

“Congratulations,” L said. “You have in your hand the most Toronto record ever pressed: a groove designed in an elevator repair shop by a drummer who tuned kick heads with socket wrenches. It belongs on your wall because the rest of the set is there, and because you will not sell it to whoever offers the most. You will make them talk about where they heard their first snare in a small room.”

“You make a lot of assumptions about me,” I said.

“I make a living testing assumptions,” she said. “Last step: look under your register.”

I knelt and pulled out the drawer. Taped upside down: a receipt from twelve years ago, yellowed to honor. On it: a name I knew—the former owner who taught me how to grade sleeves without lying—and below it, in that same sparing hand:

If you’re reading this, kid, it means the city decided you can be trusted. Don’t wait for the bell. Put the right things where they can hear themselves again. — L.

The mouth of my breath did something warm and embarrassing. “You knew him.”

“I apprenticed under him,” L said. “I left town for a while. I’ve been bringing strays home ever since.”

I rested my chin on the counter. “Why the pageantry? You could have knocked.”

“I could have,” she said. “But then you would have had to take my word. Now you have the word of the room. And the weight in your hands.”

“Okay, archivist,” I said, trying on the word. “What do I owe you?”

“A favor later,” she said. “Not now. Not tonight. Someday when a record doesn’t want to be sold and you can’t explain why. Call me. I’ll reroute the story.”

“Do I get a number?”

“Behind the third sleeve of ‘City Ghosts,’ under the liner notes,” she said. “And a warning: if someone comes in asking for ‘vinyls,’ you must make them say it right before you let them near the listening station.”

“That’s cruelty,” I said.

“That’s pedagogy,” she said.

The alley door clicked open softly. A silhouette paused in the threshold—the suggestion of a coat, hair tucked up, a person who could vanish or stay. L raised a hand in a brief salute.

“You really are in the alley,” I said, dumbly pleased.

“I told you the truth,” she said. “Your turn, Needle. Tell me one true thing before I go.”

I thought of all the tiny lies a shopkeeper tells—about pressing quality, about patina, about patience. I went with something boring that wasn’t.

“I water the plant because the last owner did,” I said. “And because I like the way the leaves shine when the door opens.”

“That’s two,” she said, and I heard the grin again.

“There will be more,” I said. “Come back when the storm clears. I’ll play you track 7 loud enough to make the neon blush.”

She stepped backward. The door sighed shut.

I hung the record on the wall in the small gap it had been saving for itself and wrote a new rule in the shop notebook: Put the right things where they can hear themselves again. Underlined once. No exclamation marks.

At 12:57, I counted the till again. The numbers behaved. The plant looked like it might live. The neon sign buzzed, softer now, like it had decided to try being a lullaby.

When I flipped the window sign from CLOSED to something I wrote in pencil on the back years ago—BE RIGHT WITH YOU—I realized L had given me more than a record. She’d given me a way to keep time: not by the bell, but by the way a room sighs when a missing piece finds its seat.